Having played for a few years at the nexus of academia, big pharma, and government, it is interesting to watch how these three bodies orbit each other and interact (for those of you familiar with the Three-Body Problem you know such a system is often unstable, but I digress). It is often frustrating, being a person with type 1 diabetes, knowing there are, for example, medications out there with overwhelming evidence behind them but which are not funded by government national health programs. GLP-1s are a great example. These are well established to provide benefit to people with type 1 diabetes but are still, certainly in Australia, not covered and financially out of reach for those who would benefit.

So, what does it take to get something approved for government subsidy? I see four major factors which are necessary, and I thought I would write this article to describe them. For context, I will use the subsidy of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) for people with type 1 diabetes (T1Ds) in Australia as a case example.

The ‘Ask’

The first step is a clearly articulated ask: “We would like the government to fund/subsidise <x>”. In the case of CGMs for T1Ds, the ask is “We would like the government to fund/subsidise CGMs for T1Ds”. In reality, the ask for was for a specific subset, and the program was expanded to all T1Ds over time (for reasons explained later), but I will keep things simple to illustrate the point.

It is, at this stage, where we can answer why GLP-1s are not available for T1Ds in Australia. The fact is, in the case of Ozempic, Novo Nordisk has not asked because they have no need to. Demand is outstripping supply such that Novo can set the price as they wish and run their factories at full speed. Asking will create a new audience which they cannot serve and force a negotiation on price. There is no motivation to do this until general demand abates or supply can be scaled up.

The Medical Benefit

The ‘Ask’ needs to be justified by a tangible benefit which can encompass quality of life measures and overall health measures. In the case of CGMs for T1D, subsidy would allow more people to access the technology and significantly reduce the need for finger pricking. Near-real-time tracking of glucose levels would reduce the risk of serious hypoglycaemia and hospitalisation. All good things and a great improvement for the lives of people living with type 1 diabetes.

The Medical Benefit provides the “So What?” element to the request and can be very emotive. A piece of wisdom often used in sales is people make decisions on how they feel about the purchase and justify it with logic after the fact. The Medical Benefit is the door to stirring the heart of government to act and, in turn, makes for an emotive tale for voters for justify the spend and show the government cares.

The Evidence

A good tale still needs evidence. Aristotle’s ‘Art of Rhetoric’ speaks of three key elements necessary to persuade:

- Ethos: The argument should be from a credible body

- Pathos: The argument should stir the emotions of the receiver

- Logos: The argument should be based in reason

I have taken it as given that, if a request is being made, for it to get the ear of the government, it will need to be from a credible source (Ethos). The Medical Benefit is the key to providing Pathos and clinical/world evidence is the key to Logos. Without evidence, it is a stirring tale but an unjustified one. A government needs to back decisions on reason otherwise the opposition will exploit the weakness.

In the case of CGMs for T1Ds, there was a wealth of clinical evidence showing improved health outcomes with the use of CGMs. I gave an example of this back in 2021 in the context of PWD pregnancy and the use of CGMs.

The Economic Benefit

Governments are required to be fiscally responsible because of scarce resources. In short, if the government is to spend a dollar, it needs to do so on whatever yields the most benefit. For medical interventions, economic justification is usually measured in cost per QALY (Quality-Adjusted Life Years). Basically, a threshold needs to be met where the cost generates a minimum level of benefit which, in this case is a longer and better quality of life for the individual.

The threshold varies from country to country and, while there is no official limit in Australia, a general rule of thumb is government will consider a medical intervention which costs less than $50,000 per quality adjusted life year.

In the case of CGMs for T1D, the economic numbers came out at around $30-35k per QALY and the request was approved.

Case Example: Automatic Insulin Delivery for T1Ds

Let us consider a couple of items being discussed in the diabetes community at this time. The first is equitable access to insulin pumps and, by extension, looping (Automatic Insulin Delivery aka AID) for all Australians. In Australia, while CGMs are subsidised by the government for T1Ds, pumps are not and need to either be purchased directly or obtained through private health insurance. Given a pump costs literally thousands of dollars this puts it out of the reach of many Australians and I recently helped co-author a petition to help get this changed which I encourage you to sign (QR code below).

So, based on the four elements mentioned above, how would we expect the request to fare if raised by a credible body to government as part of, say, the Inquiry Into Diabetes?

The ‘Ask’: This is relatively straightforward i.e. “AID systems should be subsidized for T1Ds”

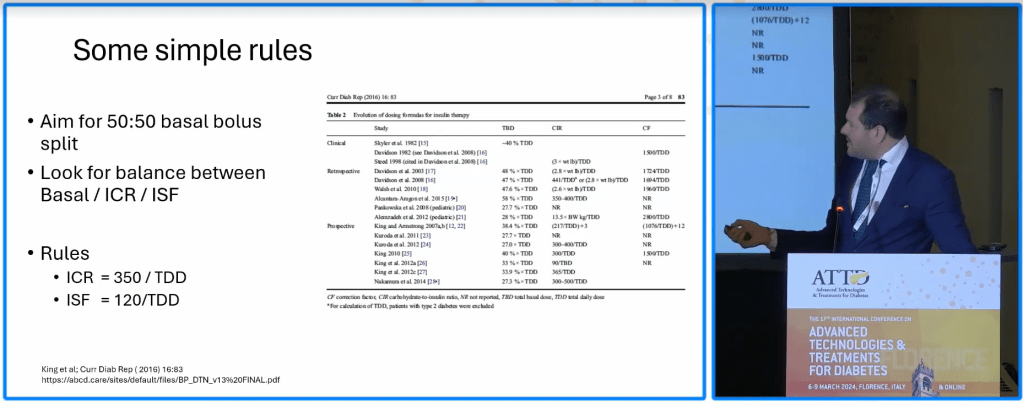

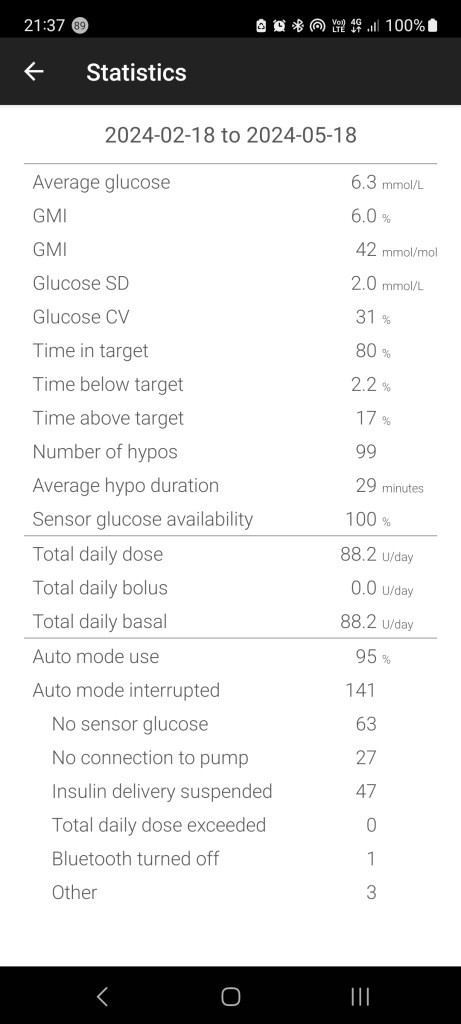

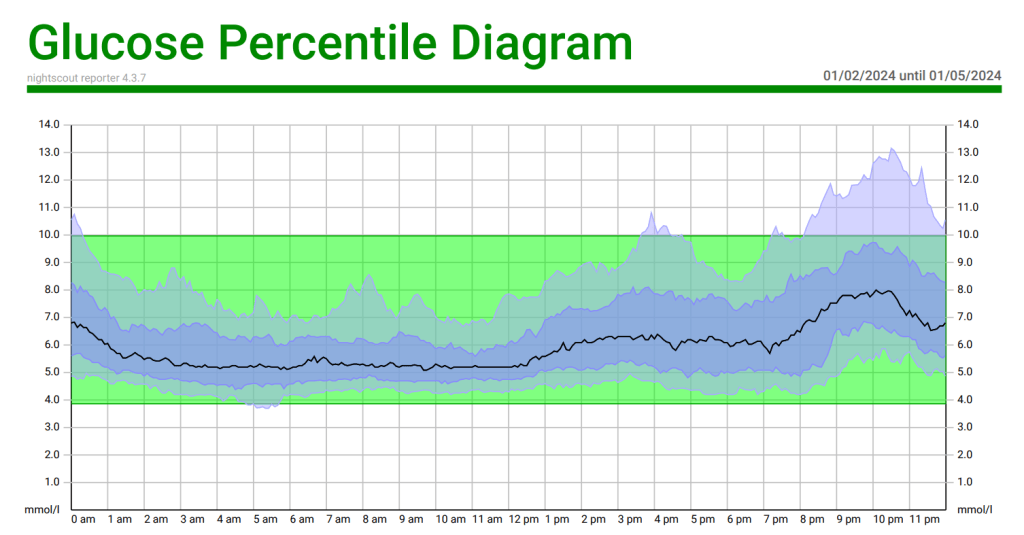

The Benefit: Lots of qualitative and quantitative benefits to AID systems such as better overnight control, improved HbA1c and Time in Range, and less manual intervention by the T1D.

The Evidence: Lots of clinical and real-world evidence to support this from companies such as Medtronic.

The Economic Benefit: While it would be great to subsidise AID systems for all T1Ds, to get the appropriate cost per QALY, it may be necessary to pick a sub-group e.g. children (who consistently have higher HbA1cs than their older counterparts in trials), T1Ds who are pregnant and so on. Generally, the cohort selection will be driven by The Evidence as this informs the economic modelling. In other words, if there are no studies of AID systems helping pregnant T1Ds, it will be harder to economically justify their inclusion.

Case Example: CGMs for People with Type 2 Diabetes (T2Ds)

On the back of the benefits seen in T1Ds with the use of CGMs it makes sense to expand the program to T2Ds.

The ‘Ask’: Again, this is relatively straightforward: “CGMs should be subsidised for T2Ds”

The Benefit: T2Ds being able to see how food affects them will inform eating habits and improve health outcomes.

The Evidence: There is some evidence of benefit for insulin dependent T2Ds but the body of evidence for general benefit is still being gathered with limited long-term studies to justify The ‘Ask’. To quote this last paper, literally written this year, “…few studies reported on important clinical outcomes, such as adverse events, emergency department use, or hospitalization. Longer term studies are needed to determine if the short-term improvements in glucose control leads to improvements in clinically important outcomes”

The Economic Benefit: Without evidence to act as a foundation for the modelling, it is harder (not impossible) to determine a cost per QALY. The best hope would be to exclusively focus on where there is evidence (insulin-dependent T2Ds) with the hope that, as more evidence is acquired, the program can be expanded to the wider T2D population.

Conclusions

It is easy for us to be frustrated with the glacial movement of governments to get behind the latest advances in technology and medicine when it is clear, for those of us at the coalface, there are benefits to many, many people. However, as we can see, with competing priorities, it is important government spending is used as effectively as possible.

The inclusion of medical interventions in national health programs requires collaboration of all three bodies (big pharma to provide the intervention, academia to show it works, and government to provide the funding) and the will by all of them to drive it. Without this willingness and the elements mentioned above it is hard, if not impossible, to achieve success.