As this is quite a long article, for those who prefer the destination than the journey, we have a tl;dr section at the end which summarises the findings.

For a review of Low Carbohydrate Diets (50-130g carbs/day) go here.

Questions covered in this review are:

- Does a VLCD lead to a lower HbA1c?

- Is the Lowest Possible HbA1c a Good Thing for Type 1 Diabetes?

- What are the Complications Associated With a VLCD?

- Does a VLCD Give Me All the Vitamins and Minerals I Need?

- Is a VLCD Sustainable?

Why Do a Review?

There are a lot of suggestions on social media about how to live well with type 1 diabetes. Some of them directly contradict each other. At one end of the dietary spectrum we have the ‘Mastering Diabetes‘ folks who promote a plant-based diet with minimal animal products, reducing insulin resistance (which even type 1s have) and, therefore, the amount of daily insulin required (bolus and basal).

At the other end of the spectrum, we have the folks like the Type 1 Gritters. They strictly follow the teachings of Doctor Richard Bernstein who promotes a very low carbohydrate diet (30g/day) with intense exercise to manage diabetes. The thinking here is that while insulin resistance may temporarily rise with the additional fats in the blood (possibly offset by the exercise), the sheer lack of carbohydrate in the diet means bolus insulin requirements are significantly reduced. Doctor Bernstein, who has lived with type 1 diabetes most of his life, has had tremendous success with his approach and is now coming up to 90 years old.

Doctor Bernstein documented his approach in a book called Dr. Bernstein’s Diabetes Solution. While excellent at describing the fundamentals of what type 1 diabetes is, unfortunately the book is now over ten years old and, in regard to technology, is quite out of date. The book dismisses continuous glucose monitors (although Dr. Bernstein now verbally supports them), insulin pumps, and flatly denies the existence of looping technology. For more contemporary wisdom from Dr. Bernstein, he has his YouTube channel, Dr. Bernstein’s Diabetes University. When I was first diagnosed, I watched practically every video on the channel and read the book (except the chapters on using insulin which, at the time, were not relevant to me). I took from it what made sense and parked the rest. It was an excellent foundation.

In the case of Dr. Bernstein, his diabetes management, informed by his health care team, was not working for him. Rather than be a passenger in his diabetes care, he started monitoring his blood glucose levels, determining what foods worked for him (low carb ones) and found a path which gave him success; the path he documented in his book so others could learn from his knowledge and experience. He ignored the zealots, did his own research, and adopted what worked for him. Every person with type 1 diabetes should be their own advocate, ignore the zealots, take control, determine the goals they wish to pursue, and find their path, just like Dr. Bernstein did.

Sadly, as if often the way with old texts, they are interpreted differently by different people. For me, the book was informative and gave me an approach to find my own diabetes management plan. It gave me permission to give critical thought to the advice of outsiders (including Dr. Bernstein) and make my own mind up. For others, like the Type 1 Gritters, it is a text which should be followed to the letter. I often bump my head against folk on Twitter who believe their goal (normal blood sugars) is the only goal which should be pursued and their approach (Dr. Bernstein’s Diabetes Solution) is the only approach to follow. Even when I have shown you can achieve superior results by embracing technology and NOT following Bernstein’s strict dietary plan, they continue with their dogmatism, the same kind of zealotry Dr. Bernstein fought all those years ago.

I am happy to give them the benefit of the doubt though as part of having critical thought is to listen to your detractors, consider their position and examine the evidence. This is what this article seeks to address. What evidence in the literature is there supporting a very low carbohydrate diet?

What is a Very Low Carbohydrate Diet?

In researching for this article I found academic literature, to allow for comparison, has broadly settled on the following definitions:

- Very Low Carbohydrate Diet (VLCD): <50g/day carbohydrate

- Low Carbohydrate Diet (LCD): 50-130g/day carbohydrate

Dr. Bernstein’s Diabetes Solution sits within the VLCD camp. I generally aim for LCD augmented with closed looping, which works for me in achieving my goals of having a sustainable/manageable approach and reducing my risk of long-term complications.

The Search Criteria

To find the articles, I used PubMed. PubMed is an online database for peer-reviewed medical articles and an excellent source for the latest research in diabetes. I try to review the latest findings once a month, collate questions, and discuss them with my endo when we meet.

My search was for the key phrases: “low carbohydrate” and “type 1 diabetes”. I had no interest in individual cases; if I wanted to hear about one person who got amazing results, I would go to Twitter and listen to the grifters selling their ‘services’. Group studies which show how the average person with type 1 achieves success with a VLCD was my target. I also wanted the full text of the paper to be available, so it could be debated openly, and a focus on quantitative information, not qualitative. The regimen being studied had to be VLCD with a focus on 30g or less/day diets, if available.

All up, the search returned a little over 90 papers. Where a paper made reference to another paper which could be of interest, I also followed the link and applied the same rules as above.

Does a VLCD lead to a lower HbA1c?

Yes it does! We have a few proof points of this. The first is “The glycaemic benefits of a very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet in adults with Type 1 diabetes mellitus may be opposed by increased hypoglycaemia risk and dyslipidaemia“. In this study 11 adults, who had been on a ketogenic diet (<55g/day) for an average of 2.6 years were studied and the following results found:

- Average HbA1c was 5.3%

- 0.9 hypoglycemia episodes per day

- “Total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio, and triglycerides were above the recommended range in 82%, 82%, 64% and 27% of participants, respectively”

The second study which talked at the average HbA1c I have mentioned in previous blogs: “Management of Type 1 Diabetes With a Very Low-Carbohydrate Diet“. This was a survey of the Type 1 Grit Facebook group. Of the 1,900 members of the group at the time, 316 responded with around half of these providing medical data. The following results were found:

- Average time following a VLCD: 2.2 years

- Average HbA1c was 5.67%

- Average daily carbohydrate intake was 36g/day

- 1 in 50 reported being hospitalised for hypoglycemia

- Noted a correlation between HbA1c and carbohydrate consumed i.e. an increase in HbA1c of 0.1% for every additional 10g of carbohydrate consumed daily

- Majority of respondents had dyslipidemia (abnormal cholesterol)

The two studies confirm that it is possible to get into the low 5% range with a VLCD. However, if someone is trying to convince you that a VLCD can consistently generate sub-5% HbA1c’s the odds are they are trying to sell you something because the evidence is simply not in PubMed.

There are two other commonalities between the studies. The first is dyslipidemia (abnormal cholesterol). If we believe these two studies are typical of VLCDs then it is reasonable to expect cholesterol results which will make your doctor frown. If cholesterol levels are important to you then a VLCD may work against you or will need to be managed.

The second commonality is the groups studied were not necessarily a random sample. In the case of the first paper, it is simply not stated where the participants came from; all we know is they were on a ketogenic diet for a number of years. In the case of the second, they came from a group dedicated to strictly following Dr. Bernstein’s approach. To join the group, participants have to pledge they follow Bernstein to the letter and have done for a “long period of time”. Here is an image of the application form to join the group.

Of those who make this commitment we have those who took the time to respond to the survey. In my mind this will also be a biased sample of those willing to share their success. It makes no sense to me that a group so committed to the cause would admit significant failure. Therefore, I see these results as the best an average person could hope for in adopting a VLCD, rather than an average or below-average measure.

A third study, “Safety and Efficacy of Eucaloric Very Low-Carb Diet (EVLCD) in Type 1 Diabetes: A One-Year Real-Life Retrospective Experience“v took 33 people with type 1 diabetes from an Italian clinic and switched them to a VLCD (<50g/day) for 12 months. Not surprisingly, in this case, the results were not as spectacular. The average HbA1c went from 8.3% at the start to 6.8% at the end.

Comparing to my own results, my HbA1c was last measured at 5.6%. This is better than the Type 1 Grit average without the need for a strict diet OR the exercise. However, for someone struggling to get their HbA1c below 7%, choosing a lower HbA1c as a goal to pursue, and indifferent to abnormal cholesterol levels, the VLCD may make sense.

Is the Lowest Possible HbA1c a Good Thing for Type 1 Diabetes?

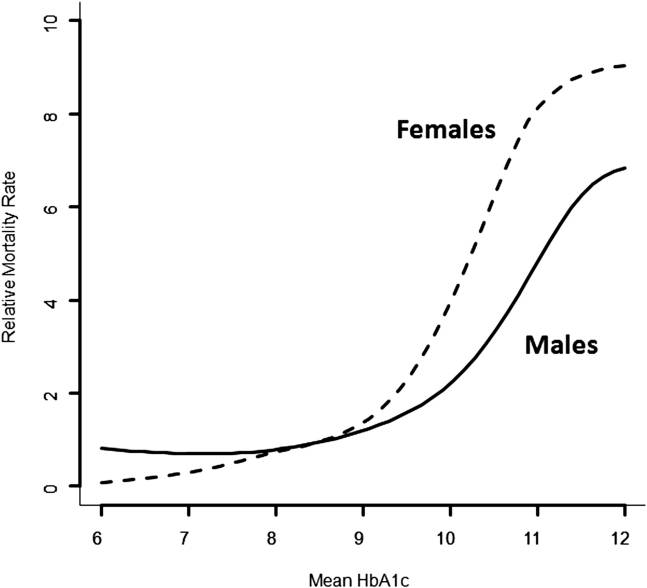

Of the papers found through this process, some talked at the correlation between mortality rates and HbA1c. The first: “Mortality in Type 1 Diabetes in the DCCT/EDIC Versus the General Population” took a group of just over 1,400 people with type 1 diabetes and compared them to the general US population. They found that an HbA1c below 8.5% meant a lower mortality rate than the general population and, as can be seen on the graph below, below 7% the mortality rate was almost flat.

When the results were split by gender, a slightly different result emerged.

For males, while still quite flat, the mortality rate actually increased below 7% and started to be higher than the general population around 6%. This was not the case for women where an HbA1c continued to drop as the HbA1c went lower and become effectively unmeasurable at 6%.

Why would males have a higher mortality rate below an HbA1c of 7%? The speculation is the increase of hypos leads to an increased risk of death.

Backing up this surprising result was a second study: “Glycemic control and all-cause mortality risk in type 1 diabetes patients: the EURODIAB prospective complications study” Examining a little over 2,700 European people with type 1 diabetes it was found the all-cause mortality rate at an HbA1c of 11.8% and 5.6% was higher than at 8.1%.

The dotted lines are for a 95% confidence interval (think of these as error bars). Again, we see a crossover point with the general population between 8-9% and a more pronounced rising of mortality risk below 7%. In the discussion, the proposed reason for the increased mortality rate at lower HbA1cs was the increased risk of severe hypoglcemia.

Given the reference range for the HbA1c in a person without diabetes tops out at 5.6%, people with type 1 diabetes face a dilemma. If they chase normal blood sugars this means, on average, an increased risk of severe hypoglycemia and an increased risk of death. Thankfully, like many complications of diabetes, they are preventable if monitored closely. In the case of hypos, a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) would help keep track of lows before they become a problem. Similarly, a looping system would automatically intervene to prevent the hypo. It is possible, as these technologies become more widespread, the HbA1c to mortality rate curve will change allowing people with type 1 diabetes to safely pursue a normal range HbA1c without concerns of a hypo. Given the data behind these curves is over 30 years old, it is possible that modern insulins have already addressed the increased hypo risk and the curve, as HbA1c goes down, is flattened today. It will be good to get new data to confirm this is the case at some point.

What are the Complications Associated With a VLCD?

We mentioned the abnormal cholesterol results earlier but some papers did mention other complications as well. “Hyperketonemia and ketosis increase the risk of complications in type 1 diabetes” speaks at the health complications of a ketogenic diet (KD) which, arguably, a VLCD is. The main focus of the paper was “oxidative stress” leading to organ damage and heart disease but it also mentioned a raft of papers discussing other complications with a KD.

Again, how important these aspects are will depend on the individual and the goals they are pursuing. Also, some of these, such as constipation, can be addressed through medicinal interventions (laxatives).

Another paper, “Low-Carbohydrate Diet Impairs the Effect of Glucagon in the Treatment of Insulin-Induced Mild Hypoglycemia: A Randomized Crossover Study” sought to compare how a person responds to glucagon, based on whether they were on a VLCD (<50g/day) or a high carbohydrate diet (>250g/day). Presumably, due to the glycogen depletion in the liver, the response to glucagon in the VLCD cohort was impaired. Again, armed with this knowledge, a person pursuing a VLCD, who intends to use glucagon to manage severe hypos, can approach the situation prepared and perhaps change their plan to manage hypos with carbohydrates instead. Another consequence, mentioned in a few papers, was the risk of eDKA because of the significantly lower insulin requirements affecting basal control of the liver, and depleted glycogen stores.

Does a VLCD Give Me All the Vitamins and Minerals I Need?

Unless appropriately managed, the evidence suggests it does not. In “Prevalence of micronutrient deficiency in popular diet plans“, a VLCD, the “Atkins for Life” diet was examined in terms of its delivery of micronutrients (vitamins and minerals). It was significantly short in providing Vitamin B7 and Vitamin E.

Similarly, in “The Impact of a Low-Carbohydrate Diet on Micronutrient Intake and Status in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes” which considered a LCD of 50-80g/day it stated “LCD may result in nutritional deficiencies, as decreased carbohydrate consumption was positively correlated with decreases in vitamin and mineral intake that were not due to calorie reduction. Thus, these decreases resulted from the LCD content rather than from reduction in calories.”

This suggests that for both a VLCD and an LCD, a multivitamin may be needed to ensure micronutrient requirements are covered, with the possible consultation of a nutritionist.

Is a VLCD Sustainable?

I am sure there are individuals who have successfully maintained a VLCD for a very long time. However, if we are talking in general terms, the evidence is not strong that this is easy to do. Even in the Type 1 Grit study, after an average of 2.2 years, the majority of the participants were failing to meet the Bernstein guideline of no more than 30g/day of carbohydrate. Other studies also believed a VLCD had troubles being maintained. “Low-Carb and Ketogenic Diets in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes” states “An issue about the use of LCD (less than 100g/day) can be the long-term tolerability. In many cases LCD was stopped before 1–2 years for a variety of reasons, often because intolerable and with a limited choice of foods” and “A clinical audit performed to assess the long-term adherence to LCD in people with T1D showed that after two years about half of the people ceased adhering…”

Even in our HbA1c studies at the start of this review the average time spent on a VLCD was no more than three years. This suggests if a person’s plan is to adopt a VLCD beyond a couple of years, they will need to ensure it is aligned to their lifestyle and has sufficient variety of food to keep it interesting. The food variety may also help address the nutritional deficiencies mentioned earlier.

tl;dr

Given the claims often made about very low carbohydrate diets (VLCDs) and the contradictory messaging about the best way to live with type 1 diabetes, it is worth examining the available evidence to see what an average person with type 1 diabetes can expect. To do this a review of the PubMed literature was performed.

While there is no doubt that a VLCD can reduce the HbA1c of a person with type 1 diabetes to below 7%, there is a need to manage the resulting risks/complications. If the person adopting the diet is experiencing an increase in hypos, these will need to be managed, mindful that glucagon is often not as effective for people on a VLCD. Cholesterol levels are often out of the recommended ranges on a VLCD and this should be managed, ideally in consultation with the person’s health care team. If it is a concern then, in the case of LDL, cholesterol-lowering medications may be recommended. Other complications, such as constipation, diarrhea, kidney stones and the more serious organ damage and heart disease, should also be monitored for and, if they arise, addressed through other interventions e.g. medication and/or diet. To ensure the diet being adhered to is nutritionally complete, either a multivitamin should be taken and/or the advice of a nutritionist should be sought. Finally, the shift to a VLCD will be, for most people a significant change in lifestyle. With many people not sticking with a VLCD beyond 2-3 years, steps should be taken to make the diet both interesting (a variety of food) and practical for one’s life to maximise the chances of success.

Based on the above evidence, I can see why healthcare professionals are often cautious to recommend a VLCD for their clients as the picture painted above is not completely glowing and, given I am already achieving better management of type 1 diabetes without adopting a VLCD, I will stick to what works for me. My next step will be to assess the literature for an LCD (50-130g/day) to see if this can achieve similar results without the severity of impact or the same complications.

One thought on “Literary Review: Very Low Carb Diets and Type 1 Diabetes”