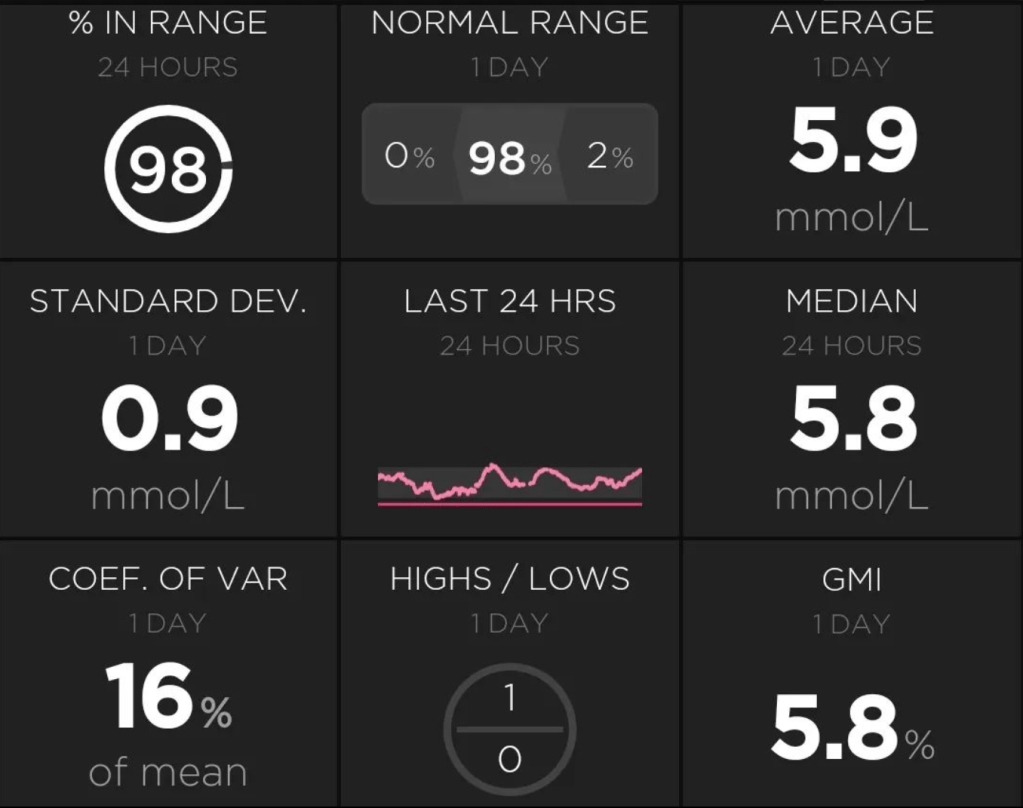

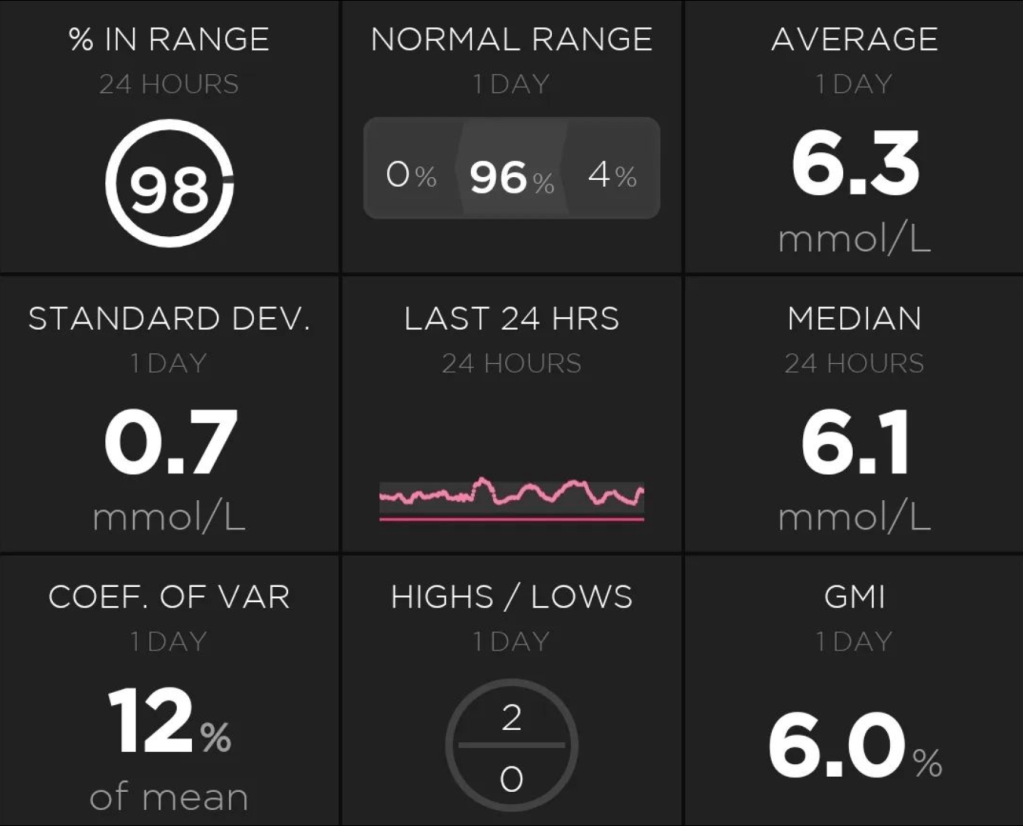

These days I use a commercial looping system (Ypsopump + Dexcom + CamAPS) but, before this was an option for me, I was using AndroidAPS (with Omnipod and Dexcom). The idea of a DIY loop can be a bit overwhelming: there are many tools and terms and it is not always easy to know where to start. To help make things clearer, I thought I would give a path, and some explanations of the tools which can, if you choose, eventually lead to a fully looping system. I am describing a path using an Android phone but there are similar paths for Apple phones as well.

Why Go With a DIY Loop When Commercial Systems Are Available?

I recently helped a young lady with type 1 diabetes and her family go in the opposite direction to me. She was using CamAPS with Ypsopump but wanted to move to AndroidAPS with Omnipod. In her case, she simply was not a fan of having tubes when the Omnipod had none. Unfortunately, in Australia, the Omnipod 5 is not available, so the obvious choice for looping was AndroidAPS. The process I am about to describe she completed in a couple of days but you can go as slow as you like. You can adopt some of the tools and then stop. There is very little by way of commitment throughout the entire process. Let us start with xDrip+.

Another reason to go down the DIY Loop path is cost. All the tools I am describing today are free.

xDrip+

xDrip+ is a tool you can download right now. No technical knowledge required. xDrip+ is an application for managing a Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM). In my setups that CGM is Dexcom but xDrip+ is compatible with Libre as well. What is great about xDrip+ is it comes with so many more features than the standard Dexcom app and is compatible with so many more phones. No more will you have to compromise your phone choice to adhere to Dexcom’s poorly maintained compatibility list. In the case of the family I was assisting, the phone they were going to was a Samsung Flip which, despite its popularity, is still not supported by Dexcom. xDrip+ worked straight away, no problems.

Some of the features of xDrip+ include:

- Ability to ‘piggy-back’ onto another application managing your sensor e.g. CamAPS

- Ability to show CGM numbers on a Wear OS watch

- Ability to capture finger pricks from Bluetooth compatible glucose meters for calibration

- Speak readings for the visually impaired

- Upload to Nightscout (I will talk about this in a bit), the Dexcom servers, and Tidepool

There are also follower apps for both Android and Apple so parents can follow along.

There really is a lot in there and the price is right (free).

To get it on your phone, click on the link above, download the latest release, open it on your phone, install it and use it to start your next sensor instead of the Dexcom app. Getting it on the phone should take no more than a few minutes. If you hate it, return to the Dexcom app when the sensor expires.

I still have xDrip+ on my phone as a “companion App” to CamAPS. This allows me to display my glucose level on the lock screen of my phone, down to my cheap Wear OS watch, and even connect it to Alexa.

Nightscout

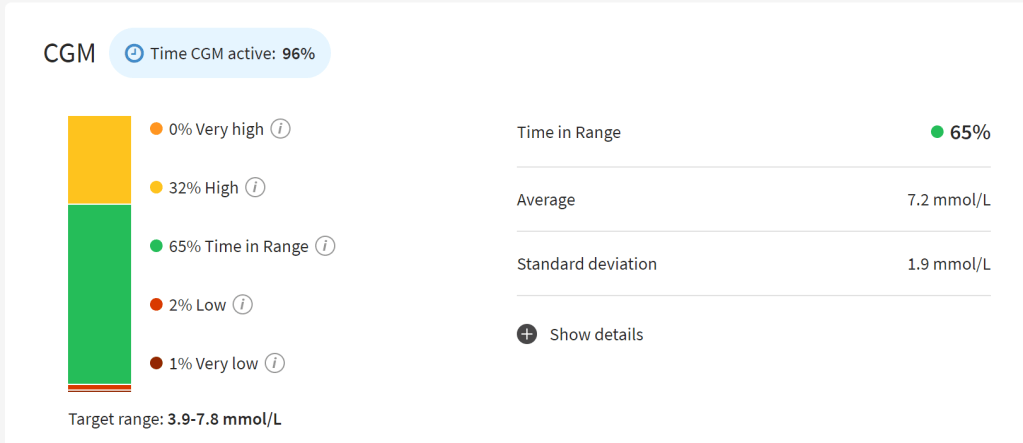

With xDrip+ installed, you can upload your data to the cloud. This means you can display your glucose level on a web browser along with other key data such as how old the sensor is (and pump information but we will get to that later). This is another way to allow followers to track your levels and receive alarms.

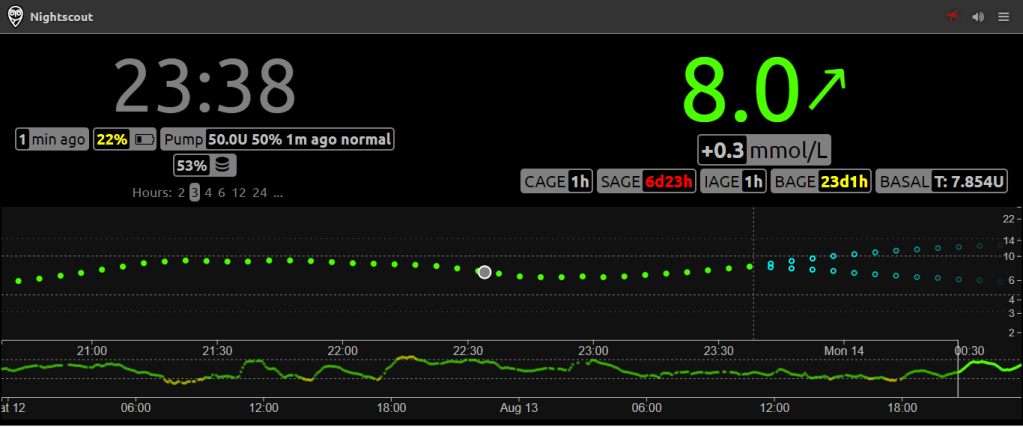

I find Nightscout to be a great way to see all my d-tech information in the one place.

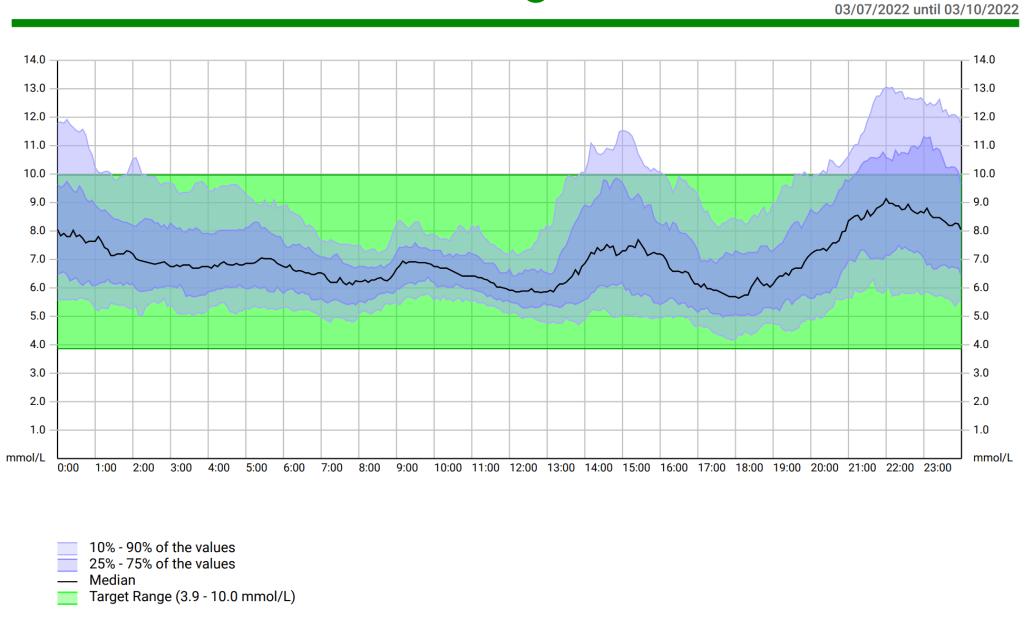

Here, for example, I can see the CGM trace for the last 24 hours, how much insulin my pump has left (>50U), the charge level of my phone (22%), how old my pump cannula and insulin is (1 hour), how old my sensor is (6 days 23 hours), the age of my pump battery (23 days 1 hour) and my current basal rate (7.854 units/hour).

Every morning I open this up to check whether there are likely to be any interruptions during the day so I can plan for them.

Another nice feature or add-on, if you like, to Nightscout is Autotune.

By giving it access to your data in Nightscout, it can analyse the data and give recommendations for adjustments to your basal profile and IC ratio. Running this to help tune your loop or before you start looping to ensure your fall-back profile is reliable gives a lot of peace of mind. I spoke about how I do this tuning here.

To get Nightscout going, follow this excellent video by Scott Hanselman. This will get you up and running in 30 minutes to 1 hour.

AndroidAPS

Once you have the previous two going, you can start down the path of AndroidAPS. AndroidAPS is an app which allows for looping i.e. it bridges the gap between your CGM and pump so they talk to each other and automatically manage your blood glucose levels. The full documentation can be found here. If it seems overwhelming, my suggestion is read the ‘Getting Started’ and ‘What Do I Need’ sections in full and then walk through the step-by-step build instructions. Building the APK file may take an hour or two and then you can add it to your phone, as you did with xDrip+. As with everything else, this will cost you nothing but a little time.

Please note that, even with the app installed, there is still much to do before the app will allow you to loop. Before key features are enabled, you must complete the ‘Objectives’. The Objectives are actions you must perform in the app, multiple choice questions, or immersion into a feature for a limited time for you to see what it is like. To complete all of the Objectives will take a few weeks and, by the end, you will completely understand how to use the app and the features which allow it to loop.

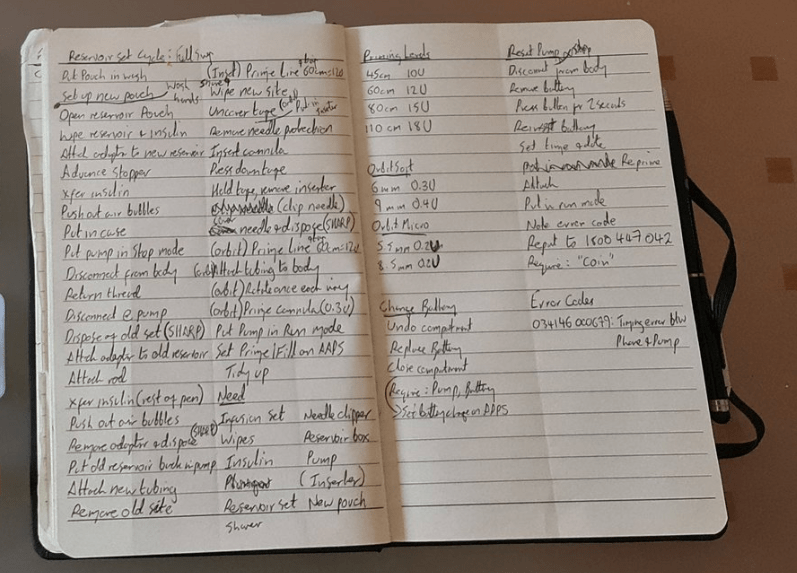

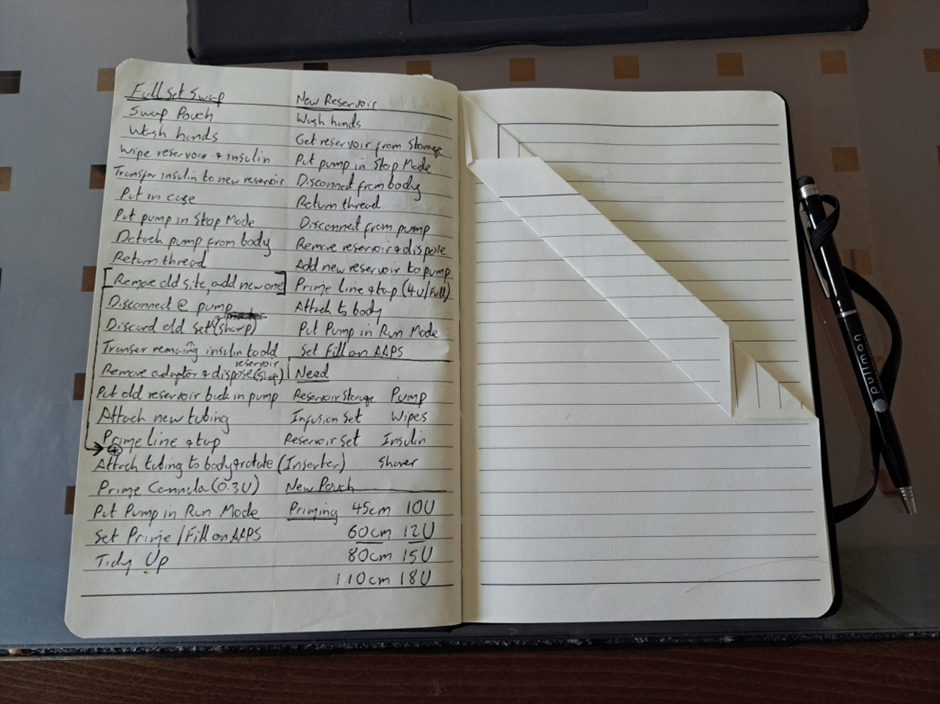

Even though I now use CamAPS, I still have AndroidAPS running , listening to xDrip+ for the CGM data and applying the loop to a virtual pump. Why bother? Because AndroidAPS still has features missing from CamAPS such as the ability to record pump set changes, and sensor changes and this where Nightscout retrieves the data from, as I upload it directly from AndroidAPS.

Conclusions

So there you have it, you can install all three, or stop wherever you like. Even if you go all the way to AndroidAPS, there is no lock-in contract and YOU decide when to activate looping. This can take as little as a couple of days to set up or longer depending on how much you want to ease in. Every step of the way you are in control and, with thousands of people running this software, you can be confident it is safe and secure.